There’s a particular kind of man who vanishes while still alive. He doesn't disappear in a dramatic act. No explosion. No news report. He simply slips out the side door of a diner, forgets how to explain what he’s feeling, or finds himself suddenly, always tired. These are the men that Somebody Else’s War, David Roy Montgomerie Johnson’s rangy and unsentimental novel, seems to understand better than most.

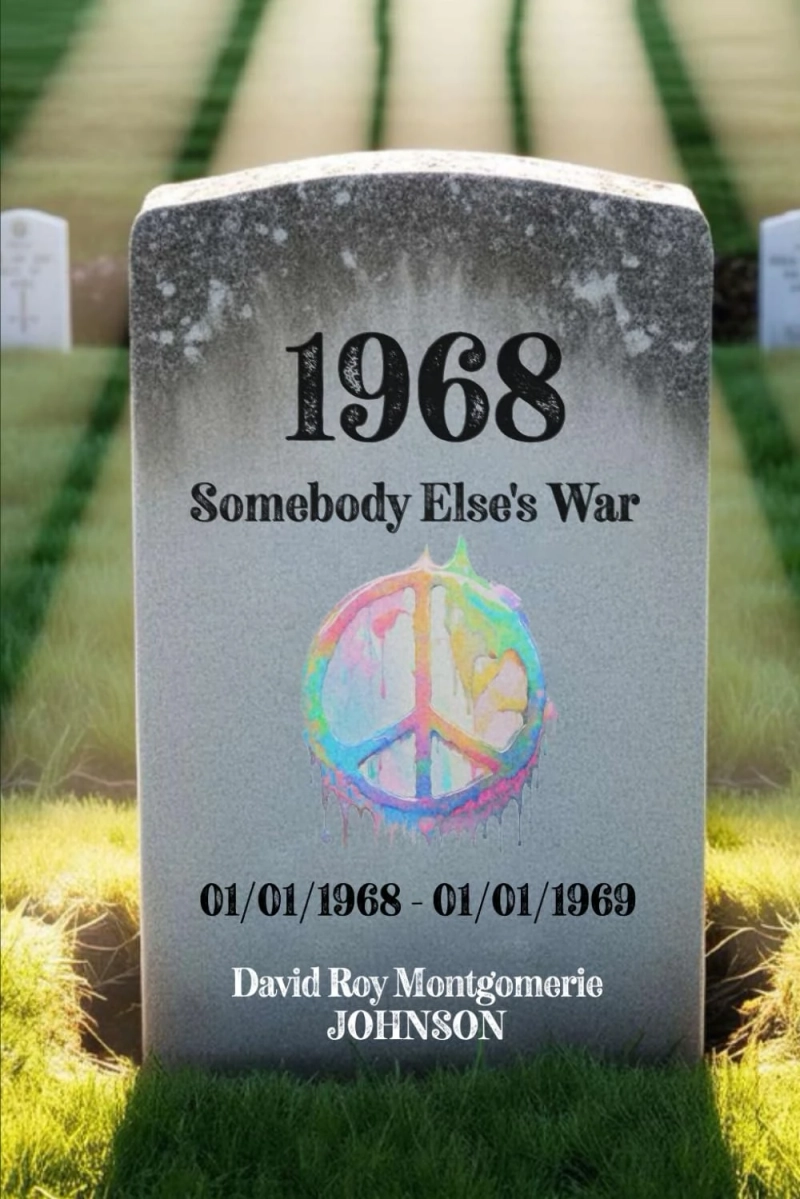

Set in 1968, the book is ostensibly about a Canadian town and its colourful collection of oddballs, drunks, politicians, aging veterans, neglected teenagers, and cats. But beneath its clever dialogue and its fond portraits of small-town absurdity, the novel feels less like a story and more like a burial ground. A slow, deliberate study of how men disappear: from history, from responsibility, from their own selves.

Captain Sammy Enfield, for example, is introduced not with a bang but a sigh. A Marine veteran now running a tiny, ineffective police department in Newport on the Lake, he wakes from nightmares in a cold sweat and immediately turns to ritual, shaving, feeding the cat, trudging five blocks through the snow. These are not heroic routines; they are tethers. He’s trying, but he’s not sure to what end. Sammy isn’t heading anywhere, he’s just trying not to drift off the map.

And this is what makes Johnson’s novel so quietly unnerving: it refuses to let men off the hook, even as it clearly sees their pain.

These aren’t the mythic men of war stories, no iron-jawed generals or tearful reconciliations. The men in Somebody Else’s War don’t even know what they’re avoiding, only that something is unfinished. Whether it’s Tubby Tuberville, the old cop running on muscle memory and nicotine, or the dangerous prisoner B11711 muttering revenge fantasies in his cell, what binds them is a deep, slow-burning confusion. They’ve inherited scripts, be brave, be silent, be useful, and they are now stumbling around with no stage left to act on.

Johnson allows these men to talk, but what’s most compelling is how often they fail to say anything of meaning. They squabble. They perform masculinity through trivia, sports scores, cars, and weather complaints. There’s a repeated failure to connect, especially with the women around them. Sammy’s estranged wife, Becky, delivers one of the book’s few direct monologues, and it's filled with frustration: a catalogue of dead Enfield men who never lived long enough to know their children. She wants to change the pattern. Sammy, meanwhile, still hopes his marriage might drift back together like a fog reforming over a lake.

The war in Vietnam threads through the novel like a distant hum, a war these characters can’t stop, won’t fight, but fear will devour their children. In many ways, it’s a ghost war. The actual violence is far off, yet its influence is everywhere. The idea of war (its inheritance, its marketing, its consequences) sits in every interaction. It’s in the way Boy Simpson walks with his dad, Gunner, a man whose past is thick with unspoken missions and hinted violence. Gunner doesn’t boast. He teaches. And in those rare, tender conversations, Johnson suggests an alternate model of masculinity: one not defined by dominance but by reflection.

This might be the most radical element in a book that otherwise avoids the theatrical. It posits that strength could be quiet. That fathers might raise children not through control but through conversation. That dignity is something grown, not performed.

Even so, not all men in Newport on the Lake are redeemable, and the novel doesn’t flinch. B11711, the inmate, is a deeply disturbing portrait of festering entitlement and unresolved abuse. His internal monologue, soaked in misogyny, racism, and pedophilic fantasy, is among the darkest passages in the book. Johnson doesn’t make him complex, he doesn’t need to be. He’s the end point of unchecked grievance. A man who sees everyone else’s agency as an insult to his own story. He’s not a victim of war but of a worldview where violence is always waiting to be justified.

In contrast, the novel’s women, while not central, serve as the moral temperature. Becky, Chrissy, the waitress with the moon-shaped scar, even the absent Maggie, each of them challenges the men around them to be more than wounded silence. But the men rarely respond directly. Johnson doesn’t force resolution where none exists. A conversation can be interrupted by a toast order. A plea for responsibility might be deflected with sarcasm. Even love, when it emerges, does so clumsily, like Sammy being called “sexy” for the first time, not because he is, but because someone finally sees past the scar on his face.

There’s a deep understanding here of how geography and emotional repression can mirror one another. Newport on the Lake is described with loving cynicism, a has-been vacation town full of rotting glory, awkward monuments, and malfunctioning infrastructure. Its police station is half-hidden. Its civic pride revolves around a clock tower that doesn’t tell time but occasionally rings at random. The symbolism is clear without being heavy-handed: this is a town suspended between eras, ringing alarms no one hears.

But even while Somebody Else's War is tragic and falling apart, it's still humorous. Really funny. Johnson's writing is really incisive when he talks about how silly small-town power is (Windy the Mayor is all show and no substance) or how tractor thefts make sense (yep, a hippy steals a Massey Ferguson in the snow). These parts don't make the novel less serious; they make it more serious. Here, laughter is a way to deal with things. At least the males can make fun of the terrible restaurant coffee if they can't talk about their misery.

What makes this book linger isn’t what it says about war but what it asks about peacetime. What do you do when the world forgets you? When the nation you served trades your story for someone younger, shinier, louder? When the wars are over, and no one told you how to live?

In Somebody Else’s War, vanishing is not a magic act. It’s a gradual wearing down. A slow replacement of purpose with routine. A silence that deepens so slowly that no one notices it until it’s complete.

And yet, the book insists, some things remain. A walk with your son. A kind word from a stranger. A cat who waits to be fed. The smallest rituals, performed earnestly, become tiny acts of resistance against disappearance.

In a culture that still struggles to imagine men as emotionally complex without rendering them tragic or toxic, Somebody Else’s War offers something rare: a portrait of masculinity that is wounded, yes, but also salvageable.

It doesn’t glorify the past. It doesn’t predict the future. But it gives us a place where we can watch the slow human work of becoming visible again. Even if just for a moment. Even if just to feed the cat.